19. January 2009

I’ve been starting to learn Octave, a maths programming language. Octave is similar to other packages that are often used to create nice graphs that you often see around the place, especially when it relates to climate change. This is a bit of a slap-dash tutorial on how to get some graphs happening with Octave. It probably assumes advanced high-school level maths.

If you wanna learn, I suggest you get QtOctave, which is damn nice, and in the Ubuntu repositories, and probably in most other distributions of linux (you can run Octave on windows – but if you really want to be this geeky, and are still on windows, you need to re-asses your values). QtOctave has a nice help-search function that lest you find most of what you need to know about functions, and installing it installs all the pre-requisites too, although depending on your distro, you might need some of the extra packages from octave-forge.

At the very bottom is an attachment with most of this code in it. I think most of this stuff will also work in Matlab, but you gotta pay for that…

Then read all of this excellent tutorial. That’s where I learned nearly everything for this tutorial, apart from the names of a few functions.

Crank out a graph!

Now you’re ready to go. Get yourself a copy of some temperature data to play with. I used NASA’s GISTEMP data. You can use any data you want, but I’ve attached a file that will do everything I’m talking about here, and includes octave-formatted GISTEMP data.

Ok, so assuming you’ve got your data in a matrix, you can then extract the relevant bits (Some of the variable names are different here to in the attachment, to save space):

% get the years from the first column

yr = GISTEMPdata(:,1);

(You did read that octave tutorial, right?)

% get the monthly averages

Temps = GISTEMPdata(:,1);

% Average them, to get the yearly means (2 refers to the second dimension, ie. average rows, not columns)

AnnualTemps = mean (Temps, 2);

You can now hack out a simple graph:

plot(yr, AnnualTemps)

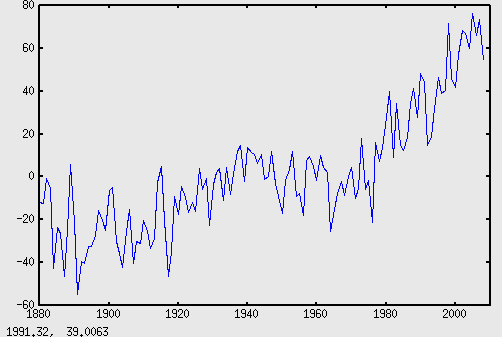

If you read tutorial, you’ll know how to adjust the axes, and add legends and titles, and all that jazz. I’m going to ignore that.

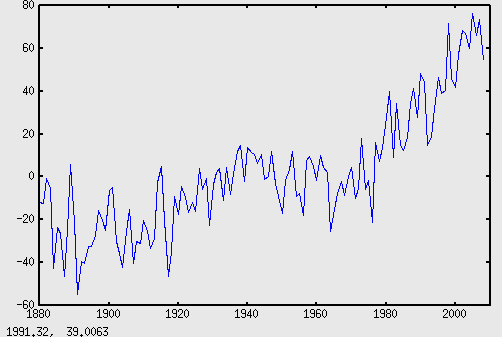

You’ll notice that the data range from -60 to 80. That’s because it’s a graph of temperature differences (anomalies) – which means that what matters isn’t the starting point, but rather, the relationships between the data. In this case, the -60 means -0.6DegC, and 80 means +0.8DegC (this is explained in the header of the GISTEMP file I linked to up top).

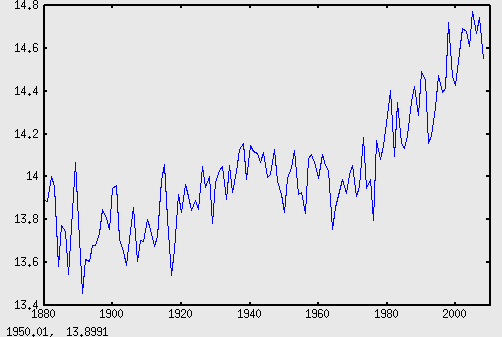

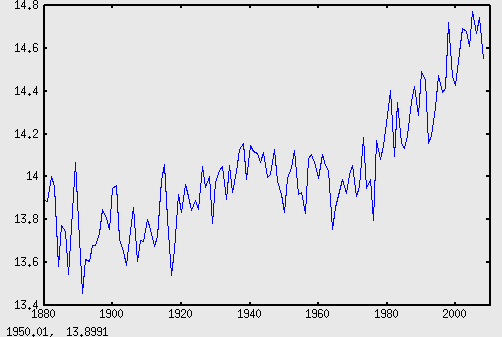

To change it to real values, to give it some human scale, we have to make the 1951-1980 average = 14DecC.

% Divide by 100, add 14, and subtract the average from the anomaly means

% 1951-1879 = 72, 1980 = 101

RealTemp = AnnualTemps / 100 + 14 - mean( mean( GISTEMPData(72:101,2:13) ) );

Cool, huh? Okay, let’s get a Trend line going.

Getting Trendy

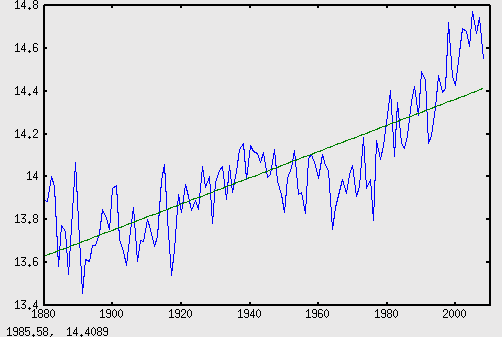

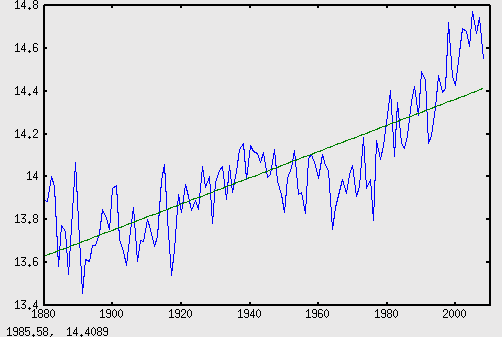

So, basically, a trend line is a best-fit line. You can do this automatically with a couple of functions in Octave, but since we’re going for just a straight trend line at the moment, we can just use a fairly simple one: a first degree polynomial fit. (a first degree polynomial is a straight line at any angle, from any starting point).

Polynomials are those equations you did in high school maths, that looked like:

y = x2+3x+1.5

That one would give you a basic parabola, shifted down and to the left a bit (I think, I haven’t actually graphed it). High-degree polynomials (where x is raised to the power of 2 or more) aren’t particularly useful for finding trend lines – they can look pretty, but don’t really help much. But more on that later. Simple first order polynomials (straight lines) are a good way of getting an idea of an overall trend.

To get the equation for the line, we need to get all the values for the basic form of a first degree polynomial:

y = mx+b

to get m and b from the data, we can use the polyfit() function, with 1, for 1st degree:

EQ = polyfit ( yr , TempReal , 1 ) ;

which provides us with an array, like:

0.0061271 2.1103472

The first value is m, the second is b. Now we apply y=mx+b:

TrendLine = EQ(1) .* yr + EQ(2)

Now you can graph the trenline, with the original data:

plot(yr, AnnualTemps, yr, TrendLine)

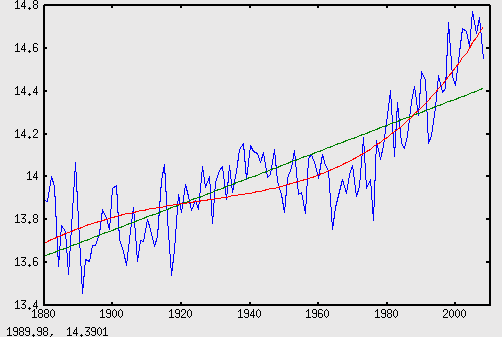

Looks ok to me. (I also note that even with the so-called “cooling since 1998/2000/2002/cherrypick”, 2008’s average temperature is almost 0.2DegC higher than the linear trend for the last 129 years..)

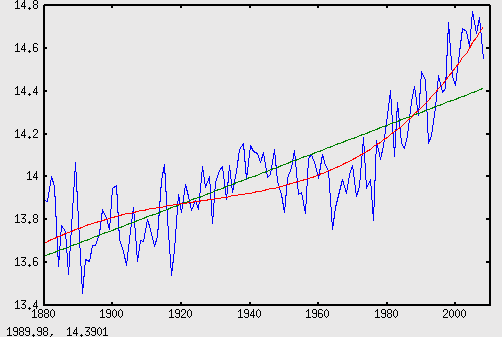

How Not To do Climate Stats

This is where the higher-degree polynomial equations come in. A high-degree polynomial can easily be made to fit a curve, but that doesn’t particularly mean anything, unless a high-degree polynomial cause can be hypothesised, that matches the trend. I don’t know of any that can.

All this was recently news, because the Australia published a piece of stupid masquerading as climate science.

Anyway, I want to show you how to do that same kind of stupid (albeit with 129 year data, not 30). You can try it with the last 30 if you like. Or with the last two. I don’t care, just don’t be surprised by the results, because they don’t mean anything.

So, we want a sixth-degree polynomial, that best fits the data we have. In other words, we want something like this:

y = rx6 + qx5 + px4 + ox3 + nx2 + mx + b

And we need to find r, q, p, o, n, m, and b. Again, we do it with polyfit(), this time with 6:

EQ = polyfit ( yr , TempReal , 6 ) ;

and we get something like:

1.3740e-16 -7.9135e-13 1.5165e-09 -9.6503e-07 -1.9859e-09 -2.5545e-12 -2.6291e-15

You might point out that these numbers are so small that they are ridiculous. To that, I’d reply: Good point.

Anyway, on with the stupidity, let’s whack those numbers into the above equation:

TempPoly6=EQ(1).*(yr.^6) + EQ(2).*(yr.^5) + EQ(3).*(yr.^4) + EQ(4).*(yr.^3) + EQ(5).*(yr.^2) + EQ(6).*(yr.^1) + EQ(7);

I hope that makes sense, it took me a while to get it.

Now we can graph it, along with the real data, and the linear trend line:

plot(yr, AnnualTemps, yr, TrendLine, yr, TempPoly6 );

Nice, huh? Now, any sane person would see without any stats education would see that an think: yep, that’s a pretty good match. Looks like a good fit to me.

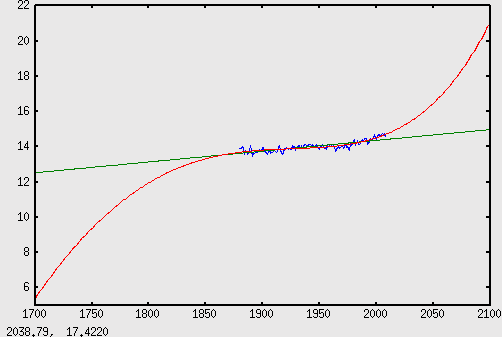

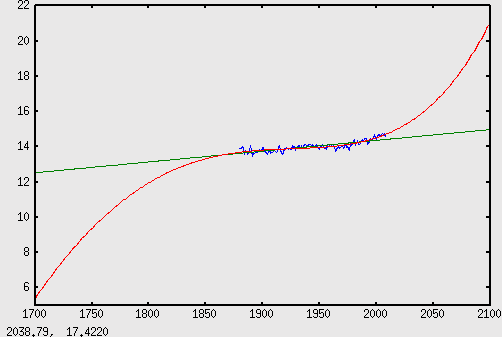

But you already know it’s stupid, so you should be looking at it with even more critical eyes than usual. One of the best ways to be critical in a situation like this is to step back, and take a wide view. So let’s see how those trend lines look if we add another century on each end: 1700 to 2100.

to do this in Octave, you need to stretch the “years” component first, then just put it back into the same equations:

yr = [1700:2100]'

The ‘ is important, it makes the vector matrix vertical. Now you can just hit the up-key to access the same lines as before:

TrendLine = EQ(1) .* yr + EQ(2)

TempPoly6=EQ(1).*(yr.^6) + EQ(2).*(yr.^5) + EQ(3).*(yr.^4) + EQ(4).*(yr.^3) + EQ(5).*(yr.^2) + EQ(6).*(yr.^1) + EQ(7);

Then just run the last plot command again, (yr has changed length though, so go back to the GISSTEMPdata for the years for the original data:

plot(GISTEMPdata(:,1), AnnualTemps, yr, TrendLine, yr, TempPoly6 );

That’s right. By 2100, temperatures won’t be 2DegC warmer, nor 4… Nope, it’s gonna be 21 degrees centigrade – 7 degrees warmer. And the “medieval warm period”? Didn’t exist. Was actually an ice age.

Disclaimer

I’m not a statistician, though I do hope to be doing stats at Uni this year. I’m reasonably sure this is all correct, though I haven’t used this kind of maths since high-school, more than half a decade ago. I learned what I now know in Octave in the last 2-3 days, so there might be better ways of doing this, I don’t know. I’d appreciate any corrections, if they’re needed, and feedback is always welcome.

I’d also appreciate any help on running a LOESS filter on the data. I don’t understand the maths except in the vaguest terms (moving polynomial average, or something?), but it seems like it applies a very useful smoothing, although it doesn’t provide any kind of future prediction the way a linear trend does (ie. in a very limited way).

ATTACHMENT:

gisstempdata.m – THIS IS A PLAIN TEXT FILE, NOT AN ODT. rename it to gisstempdata.m to use it in octave/matlab.